More beauty and brutality at The Met.

|

Sojourner Truth, "I Sell the Shadow to Support the Substance", Unknown, 1864, Albumen silver print from glass negative, 3 3/8 × 2 1/8 in |

from The Met's site;

Born Isabella Baumfree to a family of slaves in Ulster County, New York, Sojourner Truth sits for one of the war’s most iconic portraits in an anonymous photographer’s studio, likely in Detroit. The sixty-seven-year-old abolitionist, who never learned to read or write, pauses from her knitting and looks pensively at the camera. She was not only an antislavery activist and colleague of Frederick Douglass but also a memoirist and committed feminist, who shows herself engaged in the dignity of women’s work. More than most sitters, Sojourner Truth is both the actor in the picture’s drama and its author, and she used the card mount to promote and raise money for her many causes: I Sell the Shadow to Support the Substance. SOJOURNER TRUTH.

The imprint on the verso features the sitter’s statement in bright red ink as well as a Michigan 1864 copyright in her name. By owning control of her image, her “shadow,” Sojourner Truth could sell it. In so doing she became one of the era’s most progressive advocates for slaves and freedmen after Emancipation, for women’s suffrage, and for the medium of photography. At a human-rights convention, Sojourner Truth commented that she “used to be sold for other people’s benefit, but now she sold herself for her own.”

|

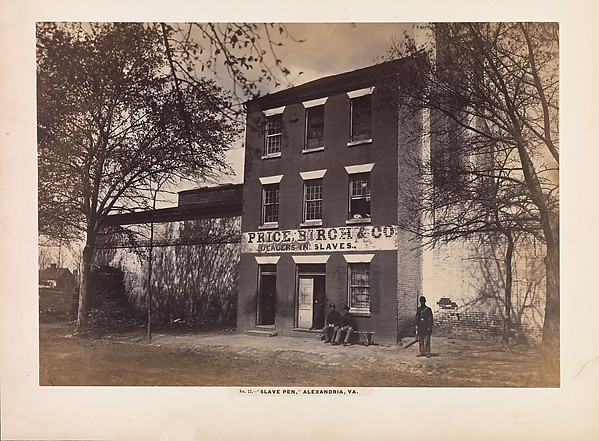

Slave Pen, Alexandria, Virginia, Andrew Joseph Russell,1863, Albumen silver print from glass negative, 10 1/16 x 14 3/8 in |

This view of a slave pen in Alexandria guarded, ironically, by Union officers shows Russell at his most insightful; the pen had been converted by the Union Army into a prison for captured Confederate soldiers. Between 1830 and 1836, at the height of the American cotton market, the District of Columbia, which at that time included Alexandria, Virginia, was considered the seat of the slave trade. The most infamous and successful firm in the capital was Franklin & Armfield, whose slave pen is shown here under a later owner's name. Three to four hundred slaves were regularly kept on the premises in large, heavily locked cells for sale to Southern plantation owners. According to a note by Alexander Gardner, who published a similar view, "Before the war, a child three years old, would sell in Alexandria, for about fifty dollars, and an able-bodied man at from one thousand to eighteen hundred dollars. A woman would bring from five hundred to fifteen hundred dollars, according to her age and personal attractions."

|

Ruins of Gallego Flour Mills, Richmond, Alexander Gardner, 1865, Albumen silver prints from glass negatives, 6 7/16 x 14 1/2 in |

|

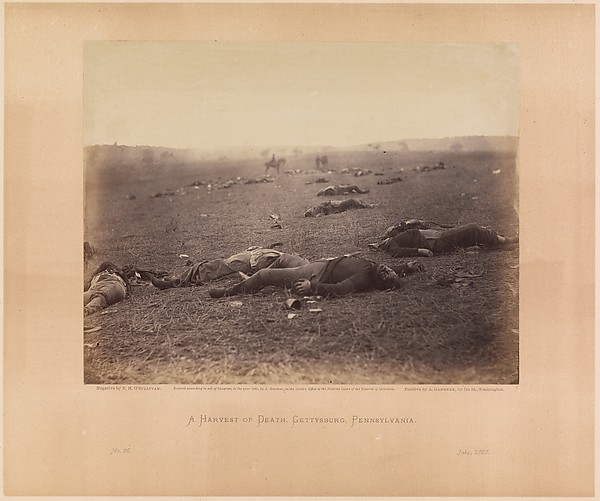

A Harvest of Death, Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, Photographer; Timothy H. O'Sullivan, Printer; Alexander Gardner , :July 1863, Albumen silver print from glass negative, 7 × 8 7/8 in |

|

Ordnance Wharf, City Point, Virginia, Thomas C. Roche, 1865, Albumen silver print from glass negative, 8 9/16 x 10 1/16 in |

|

Contrabands Aboard U.S. Ship Vermont, Port Royal, South Carolina, Henry P. Moore, 1861, Albumen silver print from glass negative, 5 1/16 × 8 3/16 in |

from The Met's site;

Moore focused his camera on the changed lives of African Americans in the aftermath of the Union victory (navy and army) at the Battle of Port Royal, South Carolina, in November 1861. With the departure of their plantation owners, coastal plantation workers were no longer slaves but, before the Emancipation Proclamation, not yet free. They were considered "contrabands," a term coined by Union General Benjamin Butler to describe their status as conscripted former slaves who had escaped the Confederacy. The U.S.S. Vermont served in the South Atlantic Blockading Squadron as a store and receiving ship, a hospital, and here as the backdrop for one of the war’s most revealing group portraits.

|

Brigadier General Gustavus A. DeRussy and Staff on Steps of Arlington House, Arlington, Virginia, Alexander Gardner, May 1864, Albumen silver print from glass negative,6 3/4 x 9 1/16in |

from The Met's site;

Here, Union soldiers pose for the camera in deliberately casual attitudes on the front steps of the Confederate commander Robert E. Lee's mansion, which was confiscated by the government in 1861. Laying blame-literally at Lee's doorstep-for the vast suffering of the Civil War. The Union Army in 1864 began to bury its dead on Lee's property in what later became Arlington National Cemetery.

|

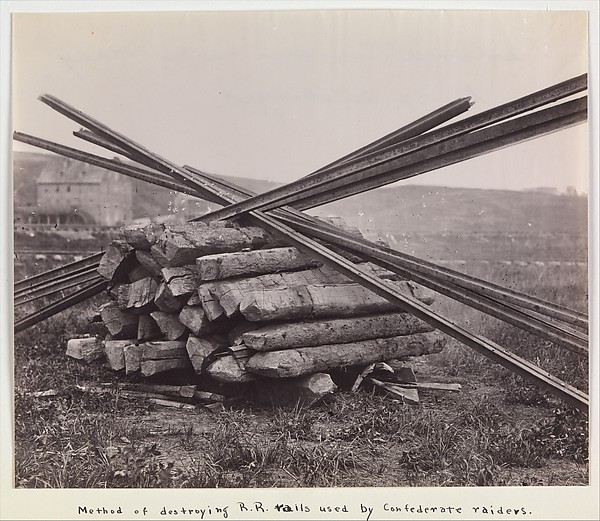

Confederate Method of Destroying Rail Roads at McCloud Mill, Virginia, Andrew Joseph Russell, 1863, Albumen silver print from glass negative, 6 3/8 × 7 11/16 in |

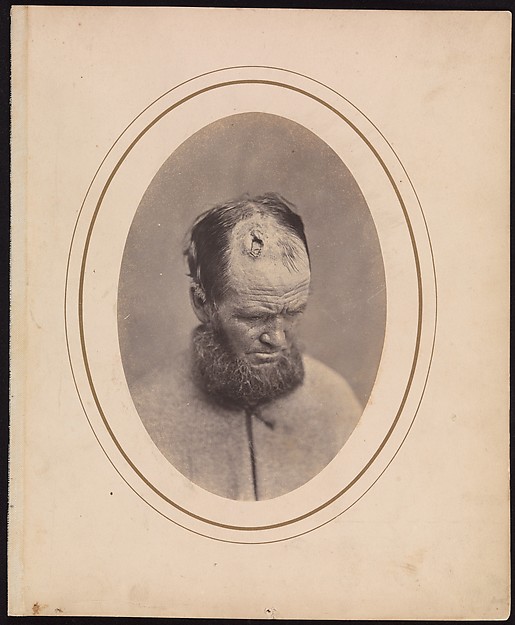

Private John Parkhurst, Company E, Second New York Heavy Artillery, Reed Brockway Bontecou, 1865, Albumen silver print from glass negative, 7 7/16 × 5 3/16 in |

from The Met's site;

Union Private Parkhurst received a gunshot wound to the head at Farmville, Virginia, in the final weeks of the Civil War. The ball fractured the upper portion of the soldier’s front bone, and he was removed to Harewood Hospital. Dr. Bontecou’s printed notes on the reverse of his card-mounted teaching photograph reveal that Parkhurst was fifty years old and that after treatment at the hospital his health progressed favorably. “Doing well,” Bontecou observed. The portrait is a good example of how at times the surgeon used enlargements to bring attention to a specific wound and its treatment. In this case, studying his patient from above, he also created a sublime document of medical recovery and human introspection.

|

Armory Square Hospital, Washington, Unknown, 1863–65, Albumen silver print from glass negative, 6 13/16 × 7 7/8 in |

from The Met's site;

...in two years President Lincoln had 187 general hospitals built, providing 118,000 beds. The majority were in the District of Columbia, including Armory Square Hospital seen here. The view shows Ward F and appears to document an anniversary of the facility, complete with flags, evergreens, and hanging flower baskets. The hospital was constructed on land adjacent to the Smithsonian Institution, approximately where the National Air and Space Museum stands today.

No comments:

Post a Comment